When Objects Are Not Enough

Tony Messias

I've been looking up resources on the roots of Object-Oriented Programming - a.k.a. OOP. This journey started because there is a trend in the Laravel community of using Actions, and the saying goes as that's what "Real OOP" is about. I had some doubts about it and instead of asking around, I decided to look for references from the Smalltalk days. That's when I found the book Smalltalk, Objects, and Design. I'm having such a good time researching this that I wanted to share some of my findings so far.

This Actions pattern states that logic should be wrapped in Action classes. The idea isn't new as other communities have been advocating for "Clean Architecture" where each "Use Case" (or Interactor) would be its own class. It's similar. But is it really what OOP is about?

If you're interested in a TL;DR version of this article, here it is:

- Smalltalk was one of the first Object-Oriented Programming Languages out there. It's where ideas like inheritance and message-passing came from (or at least where they got popular, from what I understand);

- According to Alan Kay, who coined the term "Object-Oriented Programming", objects are not enough. They don't give us an Architecture. Objects are all about the interactions between them and, for large scale systems, you need to be able to break down your applications in modules in a way that allows you to turn off a module, replace it, and turn it back on without bringing the entire application down. That's where he mentions the idea of encapsulating "messages" in classes where each instance would be a message in our systems, backing up the idea of having "Action" classes or "Interactors" in the Clean Architecture approach;

Continue reading if this sparks your interest.

What Are Objects?

An object has state and operations combined. At the time where it was coined, applications were built with data structures and procedures. By combining state and operations in a single "entity" called an "object" you give this entity an anthropomorphic meaning. You can think of objects as "little beings". They know some information (state) and they can respond to messages sent to them.

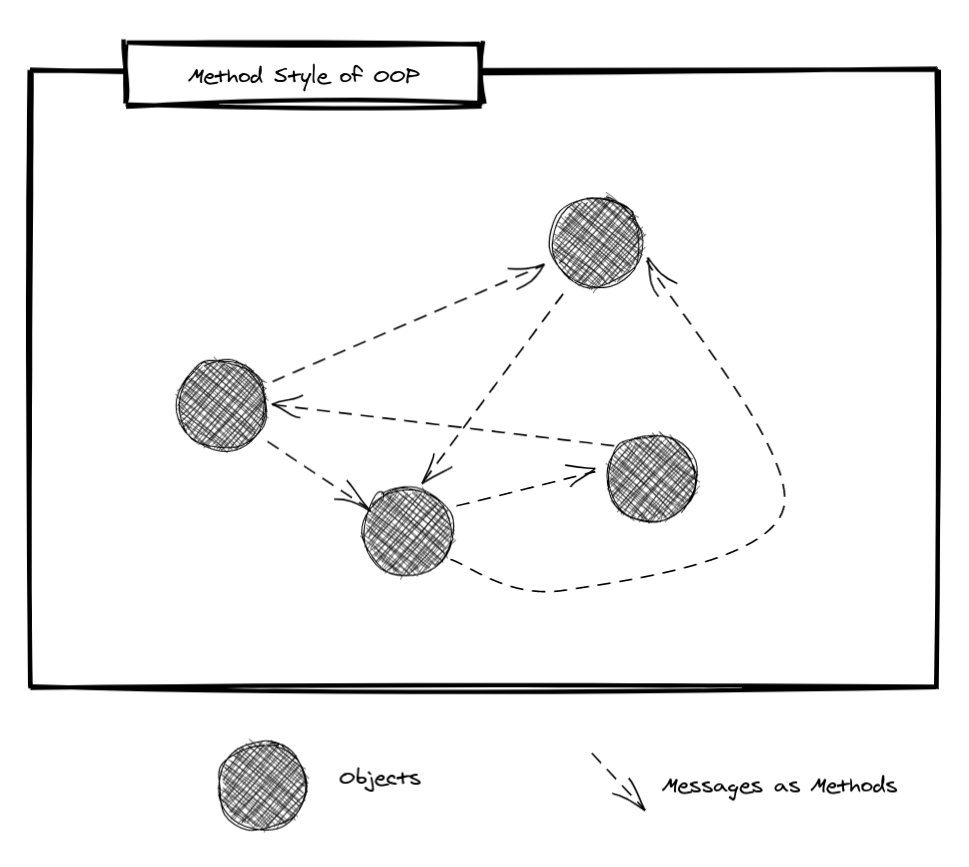

Such messages usually take the form of method calls and this is the idea that got propagated in other languages such as Java or C++. Joe Armstrong, one of the co-designers of Erlang, wrote in the Elixir forum that, in Smalltalk, messages "were not real messages but disguised synchronous function calls", and this mistake was also repeated in other languages, according to him.

One common misconception seems to be on thinking of objects as types. Types (or Abstract Data Types, which are "synonyms" - or close enough - for the purpose of this writing) aren't objects. As Kay points out in this seminar, the way objects are used these days is a bit confusing because it's intertwined with another idea from the '60s: data abstraction (ADTs). They are similar in some ways, particularly in implementation, but its intent is different.

The intent of ADT, according to Kay, was to take a system in Pascal/FORTRAN that's starting to become difficult to change (where the knowledge has been spread out in procedures) and wrap envelopes around data structures, invoking operations by means of procedures in order to get it to be a bit more representation independent.

This envelope of procedures is then wrapped around the data structure in an effort to protect it. But then this new structure that was created is now treated as a new data structure in the system. The result is that the programs don't get small. One of the results of OOP is that programs tend to get smaller.

To Kay, Java and C++ are not good examples of "real OOP". Barbara Liskov points out that Java was a combination of ADT with the inheritance ideas from Smalltalk. To be honest, I can't articulate this difference between ADTs and Objects in OOP quite well. Maybe because I first learned OOP in Java.

One more fun fact about the early days: they were not sure if they were going to be able to implement polymorphism in strongly-typed languages (where the idea of ADT came from), since the compiler would link the types explicitly and nobody wanted to rewrite sorting functions for each different type, for example (Liskov mentions this in the already mentioned talk). As I see it, that's the problem interfaces/protocols and generics solve. In a way, I think of these things as ways to achieve late-binding in strongly-typed languages (and I also think this is true for some design patterns).

Kay doesn't seem to appreciate what this mix of ADT and OOP did to the original idea. He seems to agree with Armstrong. To Kay, Object-Oriented is about three things:

- Messaging (or message-passing);

- Local retention and protection and hiding of state-process (or encapsulation); and

- Extreme late-binding.

These are the traits of OOP, or "Real OOP" - as Kay calls it. The term got "hijacked" and somehow turned into, as Armstrong puts it, "organizing code into classes and methods". That's not what "Real OOP" is about.

Objects tend to be larger things than mere data structures. They tend to be entire components. Active machines that fit together with other active machines to make a new kind of structure.

Kay has an exercise of adding a negation to "core beliefs" in our field to try and identify what these things are really about. Take "big data", for instance. If we add a "not" to it, it says "NOT big data", so if it's NOT about big data, what would it be about? Well, "big meaning", as Kay points out.

If we do that with "Object-Oriented Programming" and add a "not" to it, we get "NOT Object-Oriented Programming", and if it's not about object-orientation, what is it about? Well, it seems to be Messages. That seems to be the core idea of OOP. Even though they were promoting inheritance a lot in the Smalltalk days. And yes, messaging was a big part of it too, but since it was practically "disguised synchronous function calls", they didn't get the main stage when the idea got mainstream.

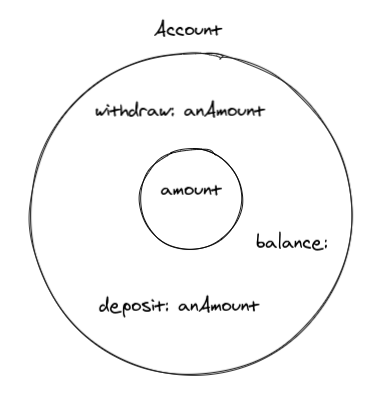

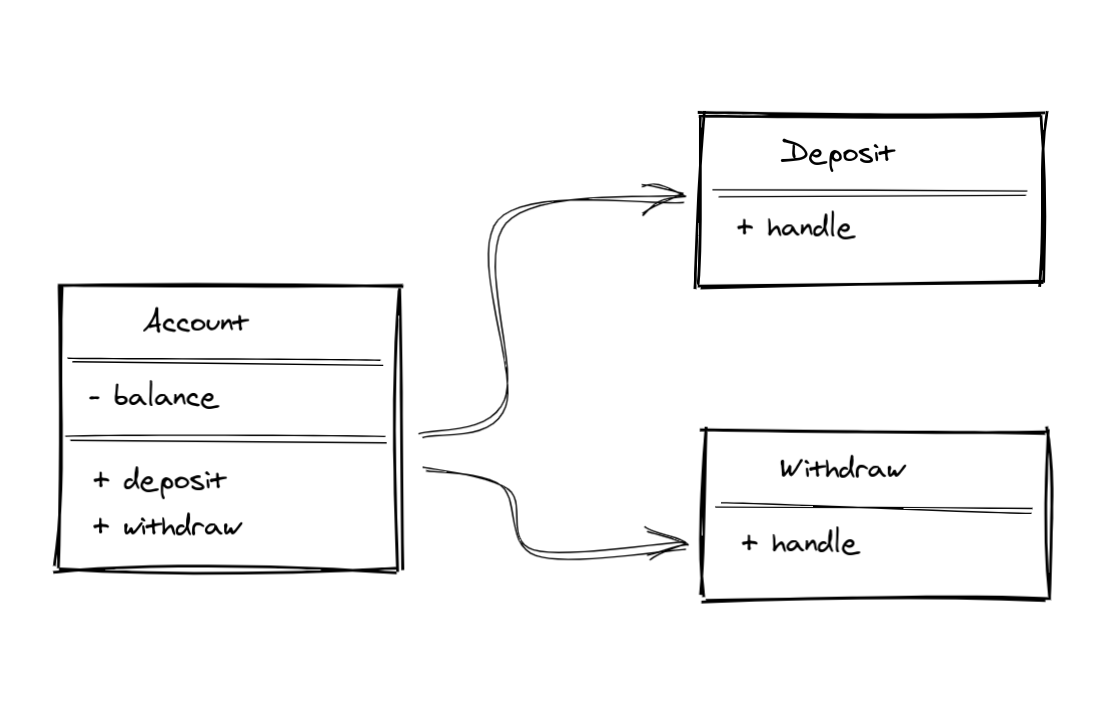

Let's use a banking software as an example. We're going to model an Account. An account needs to keep track of its balance. And it has to be able to handle withdraw, as long as the amount requested is less than the current balance amount. It also has to be able to handle deposits. The image below is a visual representation of what an Account object could be. Well, at least a simplification of that.

There are some guidelines on how to identify objects and methods in requirements: "nouns" are good candidates for "objects", while "verbs" are good candidates for "methods". That's only a guideline, which means they are "good defaults", but not hard rules.

Reification

OOP is really good at modeling abstract concepts. Things that are not tangible, but we can pretend they exist in the reality we're trying to build inside our software. They are objects (or "little beings"). The term Reification means to treat immaterial things as they were material. We use that all the time when we're writing software, especially in Object-Oriented Software. Our Account model is one example of reification.

It happens to fit the "noun" and "verb" guideline, because that makes sense in our context so far. Here's a simple example of a deposit:

class Account extends Model

{

public function deposit(int $amountInCents)

{

DB::transaction(function () {

$this->increment('balance_cents', $amountInCents);

});

}

}

Notes on Active Record

The code examples are done in a Laravel context. I'm lucky enough to happen to own the databases I work with, so I don't consider that an outer layer of my apps (see this), which allows me to fully use the tools at hand, such as the Eloquent ORM - an Active Record implementation for the non-Laravel folks reading this. That's why I have database calls in the model. Not all classes in my domain model are Active Record models, though (see this). I recommend experimenting with different approaches so you can make up your own mind about these things. I'm just showing an alternative that I happen to like.But that's not the end of the story. Sometimes, you need to break these "rules", depending on your use case. For instance, you might have to keep track of every transaction happening to an Account. You could try to model this around the relevant domain methods, maybe using events and listeners. That could work. However let's say you have to be able to schedule a transfer or an invoice payment, or even cancel these if they are not due yet. If you listen closely, you can almost hear the system asking for something.

Knowing only its balance isn't that useful when you think of an Account. You have 100k dollars on it, sure, but how did it get there? These are the kind of things we should be able to know, don't you think? Also, if you model everything around Account, it tends to grow to a point of becoming God objects.

This is where people turn to other approaches like Event Sourcing. And that could be the answer, as the primary example for it is a banking system. But there is an Object-Oriented way to model this problem.

The trick is realizing our context has changed. Now, we need to focus on the transactions happening to the account (only "withdraw" and "deposit" for now). They deserve the main stage in our application. We will promote these operations to objects, calling them transactions. And those objects can have their own state. The public API of the account wouldn't change, only its internals.

Instead of simply manipulating the balance state, the Account object will create instances of each transaction and also keep track of them internally. But that's not all. Each transaction has a different effect on the account's balance. A deposit will increment it, while a withdraw will decrement it. This serves as an example for another important concept of Object-Oriented Programming: Polymorphism.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism means: multiple forms. The idea is that I can build different implementations that conform to the same API (interface, protocol, or duck test). This fits exactly our definition of the different transactions. They are all transactions, but with different application on the Account. When modeling this with ActiveRecord models, we could have the following:

- An Account (AR model) holds a sorted list of all transactions

- A Transaction would be an AR model and would have a polymorphic relationship called "transactionable"

- Each different transaction would conform to this "transactionable" behavior

The trick would be to have the Account model never touching its balance directly. The balance field would almost serve as a cached value of the result of every applied Transaction of that account. The Account would then pass itself down to the Transaction expecting the transaction to update the balance. The Transaction, internally, would then delegate that task to each transactionable and they could update the balance. It sounds more complicated than it actually is, here's the deposit example:

use Illuminate\Database\Eloquent\Model;

class Account extends Model

{

public function transactions()

{

return $this->hasMany(Transaction::class)->latest();

}

public function deposit(int $amountInCents)

{

DB::transaction(function () use ($amountInCents) {

$transaction = $this->transactions()->create([

'transactionable' => Deposit::create([

'amount_cents' => $amountInCents,

]),

]);

$transaction->apply($this);

});

}

}

class Transaction extends Model

{

public function transactionable()

{

return $this->morphTo();

}

public function setTransactionableAttribute($transactionable)

{

$this->transactionable()->associate($transactionable);

}

public function apply(Account $account)

{

$this->transactionable->apply($account);

}

}

class Deposit extends Model

{

public function apply(Account $account)

{

$account->increment('balance_cents', $this->amount_cents);

}

}

As you can see, the public API for the $account->deposit(100_00) behavior didn't change.

This same idea can be ported to other domains as well. For instance, if you have a document model in a collaborative text editing context, you cannot rely on having a single content text field holding the current state of the Document's content. You would need to apply a similar idea and keep track of each Operation Transformation happening to the document instead.

Another example could be an PaaS app. You have provisioned servers and you can deploy on them. With only this short description one could model it as $server->deploy(string $commitHash). But what if the user can cancel a deployment? Or rollback to a previous deployment? That change in requirements should trigger your curiosity to at least experiment promoting the deploy to its own Deployment object or something similar.

I first saw this idea presented by Adam Wathan on his Pushing Polymorphism to the Database article and conference talk. And I also found references in the book Smalltalk, Objects, and Design, as well as on a recent Rails PR done by DHH introducing delegated types. I find it really powerful and quite versatile, but I don't see that many people talking about it, so that's why I found it relevant to mention here.

Before we wrap up this Reification tangent, there's one more example I wanted to mention. When you have two entities collaborating on a behavior and the logic doesn't quite fit one or the other. Or the behavior could perfectly fit either of these entities. For instance, let's say you have a Student and a Course model and you want to keep track of their presence and grade (assuming we only have a single presence valeu that can either be present | absent and single grade value ranging from 0 to 10). Where do we store this data?

It should feel like it doesn't belong in the Course, nor in the Student records. It almost feels like the solution to this problem could be to give up on OOP entirely and use a function that you could pass both objects to. Or we could maybe store that value as a pivot field in a joint table. Instead, if we reify this problem, we could promote the Student/Course relationship to an Object called StudentCourse. That would make the perfect place to store the grade and presence. These are examples of reification.

Abstractions as Simplifications

I've talked about this idea before. I have a feeling that some people see abstractions as convoluted architectural decisions and as a synonym for "many layers", but that's not what I understand of abstractions. They are really simplifications.

Alan Kay has a good presentation on the subject and he states that we achieve simplicity when we find a more sophisticated building block for our theories. A model that better fits our domain and things "just make sense".

The example of Kepler and the elliptical orbit theory that Kay uses is really good (read more about it here). At that time, there was a religious belief that planets moved in "perfect circles", where the Sun was orbiting the Earth while other objects were orbiting the Sun.

Source: NASA's Earth Observatory (link)

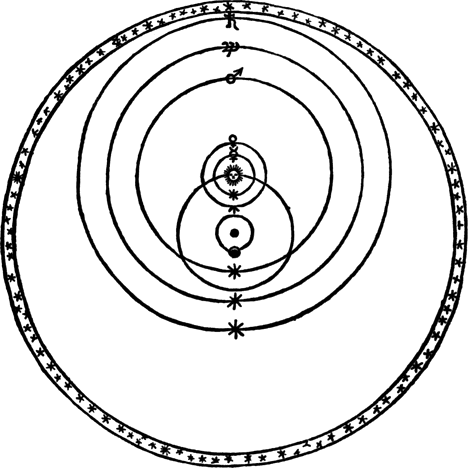

That didn't quite make sense because objects seemed to be in different positions depending on the day (among other problems), so they built a different theory where the orbits were still "perfect circles" but the objects were not going round, but instead moving in a way that at a macro level also built another "perfect circle", something like this:

Source: Wikipedia page on "Deferent and epicycle" (link)

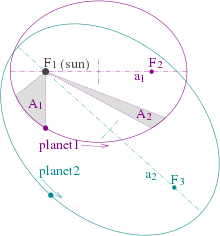

Kepler had this belief too, but after struggling to explain some of the evidences about the movements of objects, he then abandoned the idea of "perfect circle" and suggested that the orbits were actually elliptical and around the Sun - not the Earth, simplifying the model quite a lot (read this to know more about this).

Source: Wikipedia page on "Kepler's laws of planetary motion" (link)

His observation was one of the pillars of Newton's law of universal gravitation. Which later led to Einstein's theory of relativity.

The point is: the right level of abstraction often simplifies our models. Things "just makes sense" in a way that it's easier to understand than the alternatives. And it's an iterative process.

Objects In The Large

So far we've talked about promoting methods to objects. But that is not quite the same as having Actions or UseCases as classes, right? That's more about having domain models at the right level of abstraction.

In the seminar, Kay also states that objects are not enough when working on large scale systems. That's mainly because of the complexity of the systems. We want to be able to shut down, replace, and bring up parts of the system - or "modules", without affecting the entire system. Or, say, you could benefit from implementing a specific part of your system in another language because of performance reasons or a more accurate floating-point calculation.

The problem here is that we are trying to shield the messages from the outside World (our protocol). Even with all the protections that OOP provides (such as encapsulation), it doesn't guarantee that you have a good architecture.

Kay even mentions that there were 2 phases when learning Smalltalk and OOP:

- On the first phase you're delighted with it. You think it's the silver bullet you've always been looking for;

- The second phase is delusional, because you see first hand that Smalltalk doesn't scale.

One way to make OOP work on such large scale systems is to create a class for the "goals" we want to guarantee in the application. It looks like a type in a typed language, but it's not a data structure. The focus should be on the goal, not on the type. Kay uses an example of a "Print" class, where each instance of this class is a message (instead of method calls in the object). These look like what we see as Actions or Use Cases these days.

See, in Smalltalk, everything is an object. They take this very seriously. Even messages are objects internally. The difference between a message and a function call is that the message contains the receiver. In IBM Smalltalk, for instance, they even have different classes for messages with and without the receiver (look for "Message and DirectedMessage" in the manual). So when we send a message to the object, we're essentially telling the runtime to do a method dispatch on the receiver of that message. You can see that as the default goal of a message. What Kay seems to be suggesting is that we can create our own goals for our own systems. We'll explore this in a bit.

Another problem of OOP Kay describes is that we tend to worry too much about the state our objects hold and neglect the control flow (who sends the message to whom). That ends up becoming a mess. An Object sends a message to another Object, which sends a message to a bunch of other Objects, and those send messages to even more objects. Good luck trying to understand this system.

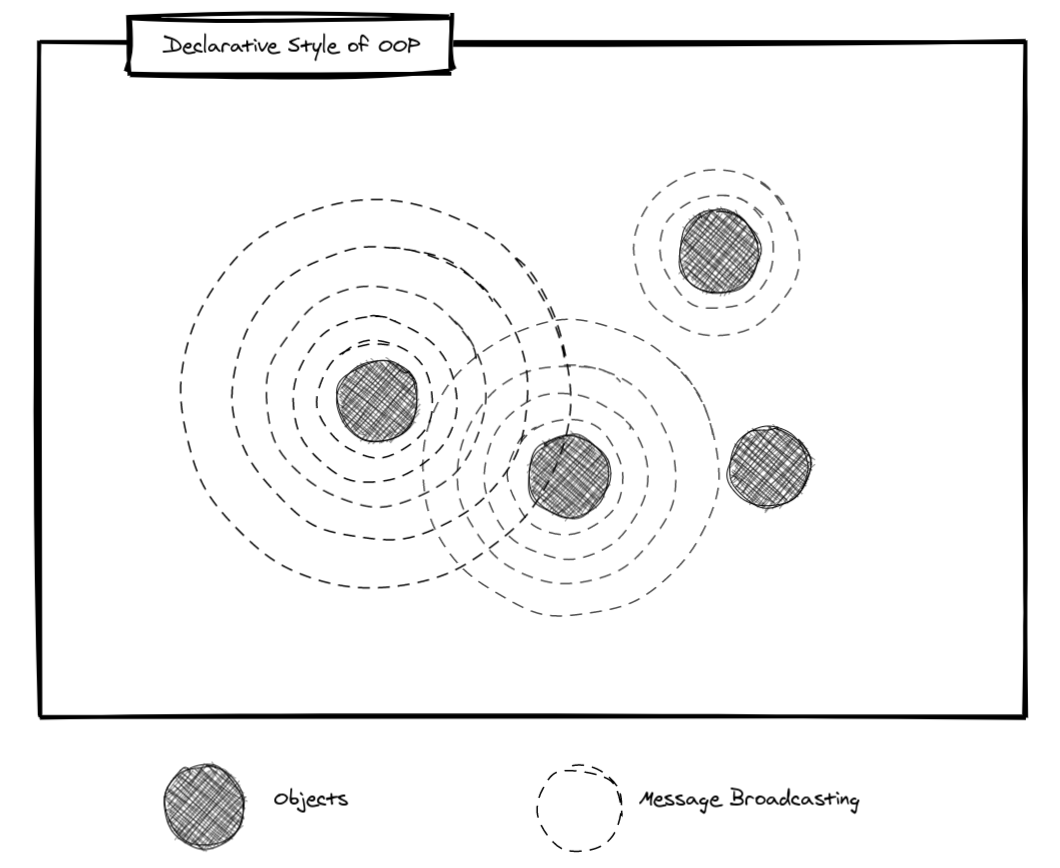

Kay suggests what resembles a Pub/Sub approach. They were exploring a more declarative approach in Smalltalk. Instead of sending messages directly to each other, Objects would declare to the system which messages they are interested in (subscribing). Messages would then "broadcast" to the system (publishing). If you have done any UI work, this should feel familiar to you, because it looks like event listeners in JavaScript.

This declarative aspect is fascinating, and it's present in some Functional Programming languages too (if you want to see where the ideas OOP blends with FP, watch this talk by Anjana Vakil called "Oops! OOP's not what I thought").

Messages as Objects

Let's explore what Kay suggests in the Seminar for a second: the idea of implementing our own goals in the system.

In our example, we could have a Deposit action in our application. It could be totally independent of the outside World (transport mechanisms - I treat the database as an "inside" part of my apps), something like:

namespace App\Actions;

use App\Models\Account;

use App\Models\Transactions\Deposit as DepositModel;

use Illuminate\Support\Facades\DB;

class Deposit

{

public function handle(Account $account, int $amountInCents): void

{

DB::transaction(function () use ($account, $amountInCents) {

$transaction = $account->transactions()->create([

'transactionable' => DepositModel::create([

'amount_cents' => $amountInCents,

]),

]);

$transaction->apply($account);

});

}

}

With this in place, our Account model doesn't need the deposit method anymore. This is the decision I have mixed feelings about, to be honest. Maybe it's fine since we promoted the Deposit message to an object as well? However, we could also implement a Facade method in the Account that would delegate to this action:

use App\Actions\Deposit as DepositAction;

class Account extends Model

{

public function deposit(int $amountInCents)

{

(new DepositAction())->handle($this, $amountInCents);

}

}

This way we would keep the behavior separate in its own object, and still maintain an easy to consume API on the Account model. That's what I feel more comfortable with these days.

One "downside" of this approach is that every dependency of the Deposit message would have to be part of the method signature of the Facade method as well. Not a big deal, and most of the time it makes sense. Say you're modelling a PayInvoice action, you would most certainly need to pass a PaymentProvider dependency to the $invoice->pay($provider, $amount) facade method (or a factory).

Also, we could use Laravel's Job abstraction here, as jobs can be both synchronous or asynchronous. This way, we would benefit from that aspect as well (dispatching a background job as a "message" to do the task asynchronously).

Conclusion

My intent with this article is mainly to share and hear back from other people what they think of this all. I'm not trying to convince you of anything. I'm making peace with this idea of having actions for behavior (as messages) myself. It sometimes feels like "procedures" where we're invoking logic by name. I'm not sure if I would use it for every bit of logic in my applications, but I think I like it when combined with Facade methods in the models.

I also found some cool design patterns that I don't see being referenced a lot. I'll blog about them soon.

Let me know what you think about this. Either tonysm@hey.com to me, tweet, or write a response article and share it with me.

P.S.: I only now found this great talk from Anjana Vakil called "Programming Across Paradigms" which I highly recommend.

P.S. 2: Some images here were created using Excalidraw

P.S. 3: As I was reading the book "Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns" I found out this was a known pattern in the Smalltalk days called Method Object. Kent Beck even states there that he was not going to include the pattern in the book, but it was really helpful once so he added it. He mentions this is useful usually in the "core" of the app when you need to interact with a bunch of objects and have temporary variables around. Another reference that suggests this should not be used for everything.

Criticism on OOP

While I was reading the book Smalltalk, Objects, and Design I found out that Dijkstra doesn't seem to like OOP (see this quora question and responses). He advocated against the use of metaphors and analogies in software (referenced, but I haven't read it fully myself), and in favor of a more "formal" and mathematical way of building software (in terms of formal thinking), as he coined the term "structured programming". But the book also mentions there is research on invention and creativity (referenced, but I haven't read it myself) that suggests that imagery fuels the creative process, not formal thinking. I found this all very entertaining to research.

Relevant References

- Alan Kay's Seminar on OOP (YouTube)

- Barbara Liskov TEDxMIT talk: How Data Abstraction changed Computing forever (YouTube)

- Smalltalk, Objects, and Design (Book)

- Laravel Beyond CRUD: Actions (Blog post)

- A Conversation with Badri Janakiraman about Hexagonal Rails (Video)

- The Clean Architecture (Blog post)

- Alan Kay's 2015 talk: Alan Kay, 2015: Power of Simplicity (YouTube)

- Joe Armstrong's (RIP) message in the Elixir Forum (Link)

- Joe Armstrong interviews Alan Kay (YouTube)

- Adam Wathan's "Pushing Polymorphism to the Database" (Blog post and Talk)

- DHH's Rails Pull Request Introducing Delegated Types (Link)

- Anjana Vakil talk called "Oops! OOP's not what I thought" (YouTube)

- Anjana Vakil talk called "Programming Across Paradigms" (YouTube)